By Mel Smith

Numerous books and many magazine articles already provide a large amount of information about the transition from steam to diesel power during the early 1960s. We therefore do not intend to go over ground that has been adequately covered elsewhere in relation to the wider historical, political and technical aspects of this period of British railway history. Instead we will consider the effect these overall changes had on the lives of ordinary people who worked on, used, or observed the railway in and around Grantham.

In a series of planned articles, and with input and help from former railwaymen, the travelling public and of course the railway enthusiast, we will take a look at how motive power, rolling stock and the railway's infrastructure in and around Grantham changed over the years. But first, to help set the scene, let’s wind back the clock and get a brief reminder of some of the key events that affected the railways as a whole.

After a rapid expansion of the railway system in the latter part of the 19th century, the early 20th century brought a period of relative stability. From 1852 railway services through Grantham had been operated by the GNR (Great Northern Railway). War had raged in Europe from 1914 to 1918 but only 5 years later, in 1923, the numerous railway companies that had been formed since the ‘railway mania' years of the 1840s were grouped into four territorial sections: namely the LNER, LMS, GWR and SR. The years that followed between the first (1914 - 1918) and second (1939 - 1945) world wars brought exciting and innovative times to the LNER's main line leading northwards out of Kings Cross to Peterborough, Grantham and beyond. In the 1930s, with growing competition from road and air transport, the directors of the LNER realised that to maintain their share of the traffic the train services between large towns and cities along their principal routes needed to be quick, reliable and, of course, comfortable. Locomotive development, the quest for speed and a stylish publicity campaign were at the forefront of the LNER’s efforts to match the threat from alternative forms of travel.

At this time worldwide media was also reporting on an emerging alternative to steam power in the form of high-speed diesel trains. A notable example entered service in May 1933 when the German State Railway's diesel-electric streamlined Fliegender Hamburger entered service, running for long periods at 85mph to keep to the scheduled timetable.

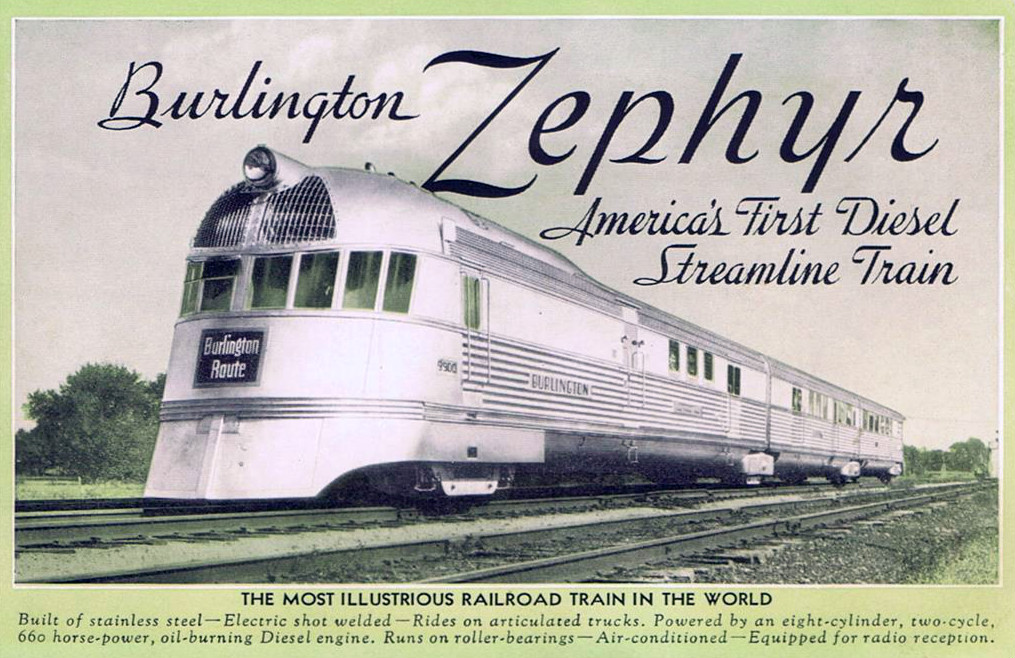

A year later, in 1934, an American diesel powered streamlined train, the Burlington Zephyr maintained an average speed of 77mph and reached a top speed of 112.5mph during a 1,015 mile journey, taking just 13 hours and 5 minutes. Ironically, the train’s nickname was ‘The Silver Streak’.

The LNER’s Chief Mechanical Engineer, Nigel Gresley, noted these developments and travelled on the Fliegender Hamburger himself. He was certainly impressed and realised the need for locomotive streamlining, albeit it was found that this was only beneficial at high speed. Although the Fliegender Hamburger (2 carriages) and Burlington Zephyr (3 carriages) were both much smaller than a typical LNER formation, Gresley calculated that a streamlined and modified steam locomotive design, based on his already successful A3 locomotives, would be able to haul trains of up to 9 carriages at similar high speeds. History, of course, tells us that the resultant modifications and trials confirmed this. With the A4 design steam power entered a new phase of high speed streamlined trains: The Silver Jubilee (1935, London to Newcastle), The Coronation (1937, London to Edinburgh) and The West Riding Limited (1937, London to Wakefield, Leeds and Bradford) .

Exciting times for the LNER but unfortunately, as we know, the late 1930s also brought growing tensions within Europe. Just over a year after the streamlined Mallard's historic remarkable run down Stoke Bank on 3rd July 1938, Europe once again plunged into war. By the end of the conflict in 1945 the LNER, along with other railway companies in Britain and indeed most of Europe, were in a pretty run down state. As 1948 dawned the railways were nationalised and the LNER itself, along with the LMS, GWR and SR, became part of BR (British Railways).

It’s now 1951 and a little short of a 100 years since the first steam locomotive had passed through Grantham Railway station. That year the BTC (British Transport Commission) approved the introduction of a new batch of ‘standard design’ steam locomotives and coaching stock for use throughout the network. At the time it was hoped that these modern locomotives would have a long lifetime, complementing or replacing the variety of pre-nationalisation locomotives that BR (British Railways) had inherited from the LNER, LMS, GWR and SR.

Despite the ongoing introduction of 'standard' locomotives, by the middle of the 1950s it became obvious that things were not going exactly to plan for BR. It seemed that a major review was the only way forward.

A combined increase in competition for freight and passenger usage, coming from both road and air transport, resulted in the government of the time carrying out a review of the railways. This review turned into a report called The Modernisation and Re-Equipment of British Railways. The 1955 report became known as The Modernisation Plan. The intention was to bring the nation’s railway system up to date. A year later, in 1956, a Government paper proclaimed that ‘modernisation’ would help towards removing BR's financial deficit by as early as 1962. The ultimate result of this meant that the previously anticipated longevity of the new 'standardised steam age' would come to a premature end in the 1960s...

The aim of The Modernisation Plan was to accelerate overall train speeds, improve locomotive and stock reliability, improve safety and increase line capacity. This was all going to be brought about by introducing various measures to make services more appealing to passengers and freight operators alike and therefore help to recover traffic that was being lost, mostly to the roads, but also to some extent to air transport. This was a new vision for the rail network in Britain, heralding the introduction of diesel and also electric power to replace the entire fleet of steam locomotives, both ageing and modern.

So the scene is set and we have (hopefully) provided you with a very basic potted history of how things evolved on our railways during their formative years, through two world wars, into the post war period and later the plan to nationally remove steam from the railway network. A selected number of companies were invited to tender for and produce a variety of diesel locomotives in line with the power range of the 'Types' as shown below.

So, what about the diesels?

The main diesel locomotive fleet would be arranged into different ‘Types’ as follows:-

Type 1 locomotives of 800hp to 1000hp

Type 2 locomotives of 1001hp to 1499hp

Type 3 locomotives of 1500hp to 1999hp

Type 4 locomotives of 2000hp to 2999hp

Type 5 locomotives of 3000+hp

DMUs (Diesel Multiple Units) would also be introduced to provide local and cross-country services.

Meanwhile, back at Grantham...

It's Saturday 21st June 1958 and the day has started like any other typical weekend at Grantham. Events in and around the station are continuing pretty much as they have done for years. Loco spotters from nearby Nottingham and Leicester and further afield have gathered to watch the usual procession of pacific locomotives thundering past at the head of through trains, or admiring close up those that pause for a few minutes on their journeys north or south. At the adjacent loco shed the intermittent hustle and bustle of everyday railway activity goes on unchanged. As usual, railwaymen are busy with their daily duties preparing for planned and unplanned engine changes. Most are indifferent, perhaps even oblivious, to the changes to come over the following five years. The next train due to pass through the station from London is already eating up the miles and has just entered Stoke Tunnel. No concern for the men of Grantham Loco for this is a through train, but its passage through the station will mark a turning point in their lives.

On the whole June 1958 had turned out to be a very disappointing wet, dull and rather cool month with unseasonal bad weather across the country. At the south end of the station a glimpse of rare sunshine has now greeted those spotters who have arrived early enough to be in place to see the Down Flying Scotsman pass through. With notebooks at the ready they are somewhat surprised to see an unfamiliar shape appear under the distant Great North Road bridge, situated to the south. For eagle-eyed spotters the skew bridge has always been a picture frame for A4s and A3s on down expresses, as well as freight trains hauled by a variety of workaday locos. Today on this damp Saturday most of the observers are puzzled by the unidentified loco framed by the bridge. For those ‘in the know’ this sounds the death knell for steam on the ECML. The mysterious shape of the locomotive's front end, rapidly closing in on them, is an English Electric (EE) Type 4 diesel electric locomotive; previously only read about in the pages of The Railway Magazine or Trains Illustrated. The loco has now passed the South Box and, with its immaculate green paintwork glinting in the sunlight, nears the transfixed group of lads positioned at their favourite spot opposite the Yard Box. With a powerful growling blast of sound and a short hoot, No. D201 tears past the astonished crowd of onlookers and thunders northwards on its way to Edinburgh.

So what was this all about? As mentioned earlier in this article, in 1955 BR had published their plan to remove steam from the railway system within the UK and replace it with electric or diesel power. Three years later, in 1958, BR’s Eastern Region took delivery of five members of a class of main line diesel electric locomotives supplied by the English Electric Company (EE). These locomotives had been designated as EE Type 4s (later becoming known as Class 40s). The famous five, assigned for use on the East Coast Main Line (ECML) out of Kings Cross Station, were numbered D201, D206, D207, D208 and D209. All of these locos were allocated to Hornsey (34B) depot between May and September 1958.

That same summer, as part of a revised 1958 summer timetable, BR introduced a number of weekday diesel hauled services on the main line out of Kings Cross. The school holiday period and longer summer evenings now gave loco spotters at Grantham the opportunity to witness this first wave of diesel hauled trains on the ECML. By the time the 1958 winter timetable came into effect the five newcomers (D201, D206, D207, D208 and D209) were firmly established on regular diesel hauled trains such as The Flying Scotsman, The Tees-Tyne Pullman, The Sheffield Pullman and other regular services through Grantham.

During 1959 and 1960 the introduction of diesels continued, with a growing number making their appearance up and down the main line through Grantham. With the arrival of the EE Type 5 prototype, Deltic, the winds of change increased in force and gathered for a full assault on steam. In the winter of 1959 this new prototype began to run trials on the ECML. By the end of 1960 the ‘Ice Cream Van’, as loco spotters at Grantham and other locations on the main line affectionately dubbed the prototype, had successfully come to the end of its ECML trials.

January 1961 saw BR take delivery of D9001, the first of a batch of 22 powerful Type 5 production 'Deltic' diesel electric locomotives that would herald the final chapter for steam services through Grantham. D9001 was named after the racehorse St Paddy later in the year, continuing (from Gresley's A3s) a popular East Coast Main Line tradition. Over the following two years the Deltics would take on legendary status and transform rail services between London and the north. At the end of the summer of 1963 the sun went down on Grantham as a staging point for steam power. In September 1963 a certain Bob Dylan penned a song (actually released in January 1964) called ‘the times they are a changin’ ...they certainly were. September 1963 saw the steam loco shed at Grantham close and only memories remained.

To be continued..............

© Mel Smith

Copyright note: the article above is published with the appropriate permissions. For information about copyright of the content of this website, Tracks through Grantham, please read our Copyright page.

Very interesting reading. thanks and appreciated too.

Glad you enjoyed it John.

Cracking article Mel, that’s it in a nutshell.

Thank you Tim. We have a lot more to follow for this section so if you have any memories of the Diesel Era at Grantham please email. In fact anyone who has a tale to tell is most welcome to send it in to us. Personal anecdotes will all help to tell the story and thereby contribute towards the history of the railways at Grantham.

It's worth making the point that the Class 40s were pretty soon found to be inadequate, hence the need for something better in the form of the Deltics. Peter Semmens in his book 'Speed on the East Coast Main Line' makes some interesting points about the relative power outputs of the A4s and 40s, showing that the 40s really couldn't cut the mustard. The problem which he describes is that as speed increases the back EMF of the traction motors increases, but this does not happen with a steam loco which can continue to put down maximum horsepower. You need a lot more h.p. in a diesel electric to overcome this, compared to a steam loco. They got this with the Deltics but the 40s were just not powerful enough, which is why they didn't last long on the fastest work.

Thanks Andy. This is just a general 'background introduction' to the Diesel Era and we do hope, without getting too technical, to cover this in some of the pages to follow. Peter Semmens book is a very good read and I have it on my bookshelf. We welcome and encourage articles and contributions from everyone who follows our efforts to cover the Grantham railway story. If you have any specific Grantham related memories, or maybe another one of your excellent articles in mind and would like to write something for this section please let us know.

Very interesting article (as always). I well remember seeing, and more to the point hearing the prototype Deltic further south up the ECML where I lived as a child at the time.

Thanks Phil, I remember the early production versions roaring past Barkston and could still be heard miles away on a summer's evening. The deltic drone ebbed and flowed in waves carried on the breeeze and was particularly haunting as dusk fell, with the only other sound the odd owl hooting in nearby Jericho Woods. Lovely memories.....

Why was it that the Scottish Region insisted on having four character headcode displays on all their diesel locos? They even went to the trouble and expense of having the nose ends of their first batch of Class 40s (I think it was D259-D271) retrofitted with them and nearly all the Class 21s that were converted to Class 29s, and at least one that wasn't - AND THEN NEVER USED THE BLOOMIN' THINGS? I cannot recall seeing ONE picture of an intra-region service with a headcode loco in charge, which is displaying the full route number. They all say "- - 1-", "- - 2-", "- - 5 -" or "- - 9 -" . Anyone any insight into the apparently somewhat flawed reasoning behind this? I'm sure plenty of "Mc40s" used to whistle and splutter through Grantham from North of the Border.