Introduction

by John Clayson

Peter and I first met when I gave a presentation of photographs to the Lincoln Railway Society. A little while afterwards Peter kindly agreed that we could meet again to talk about his memories of six years he spent as a young man working on the railway at Grantham. We chatted for a couple of hours in the cafe at Pennells Garden Centre near Lincoln and these notes, supplemented by Peter's subsequent additions and comments, are the result. They are complemented by several of Peter's own photographs. It was a sobering thought that when Peter left the railway I was just one month old!

___________________________________________________________________

Notes from a conversation with Peter Wilkinson on 9th May 2011

Peter worked at Grantham ‘Loco’ from March 1948 until August 1954, initially as an engine cleaner and then as a fireman.

Peter was brought up in Welbourn (the next village to Leadenham) where his father was the blacksmith. An early interest in the railway was encouraged by his older brother and a relative, Ernie Parr, who was a driver at Grantham.

Ernie retired on the same day that Peter started working at the Loco. He is carrying a metal toolbox. "All the drivers had them," Peter told me.

Photograph lent by Peter Wilkinson.

Peter became an apprentice joiner at the age of 14½ until he joined the railway at 15½ in March 1948.

The first year as an engine cleaner involved cleaning locomotives, setting and preparing fires and regular ‘on the job’ training in the operation and servicing of locomotives. Peter’s first trip out on the line was as an observer on the footplate of a B1 locomotive to Sleaford and back. This was on locomotive No. 61177 or 61175 (both were Grantham engines at the time).

Cleaning a locomotive was carried out in two stages. Everything below the footplating (wheels, cylinders, frames, connecting and coupling rods and valve gear) was cleaned using waste soaked in paraffin. For the boiler, cab and tender there was a polish, called ‘compo’, which looked like condensed milk. No ladders or other access equipment was provided – you had to climb the steps on the locomotive and use the handrails to steady yourself.

Another example of the cleaning tasks was ‘front rubbing’, which had to be done after steam had been raised on a ‘cold’ locomotive. Smoke filled the cab until the water boiled and enough steam pressure was raised to operate the blower and create a draught. The smoke left a film of soot over the boiler front inside the cab, where the controls and gauges were. As a cleaner you would be sent to wipe down the boiler front. You were usually given a list of engine numbers by the foreman, with times of departure, and you spent your entire eight hours or so going from loco to loco.

Photograph by Cedric A. Clayson.

Extra attention was always required to a clean a locomotive for Royal Train duty. For example the shed cleaners had on one occasion to prepare No.60044 Melton to take the Royal Train from Leadenham en route to Lincoln and the main line to Doncaster. There was a second pacific locomotive prepared as standby, and a B1 locomotive to provide steam to heat the train before departure. Having been involved in the cleaning Peter went to the station at Leadenham to watch the departure. As the train drew away he remembers the King, Queen Elizabeth and the Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret waving to him from the royal saloon.

Lent by Peter Wilkinson.

Lent by Peter Wilkinson.

The first stage of progression onto the footplate, after about a year as a cleaner, was to the role of ‘passed cleaner’ (occasionally known as ‘spare fireman’). For his firing test examination, Peter went for a trip on the footplate of a B1 locomotive with a locomotive inspector and its crew of driver and fireman. He passed the examination and became qualified to be a fireman, although up to that time he still had no experience out on the line.

Duties as a fireman at Grantham included relieving main line crew at the station, taking the locomotive to the shed yard, cleaning the fire, replenishing the coal and water and oiling round and turning if necessary, while the crew took their break in the Pilot Cabin. The pits were used for both fire cleaning and inspection and oiling, so it was a dirty job all round. On three-cylinder engines, to oil the centre big end bearing it was necessary to position the locomotive carefully so that the end of the left hand eccentric crank was level with the centre line of the axle. Then the centre big end would be at the bottom, and easier to reach with your oil ’feeder’ (a large oil container with a pouring spout) from the pit. You had to keep alert in case the locomotive moved while you were underneath it – for example by another locomotive buffering up. During the hours of darkness flare lamps were used to see by. They were often dropped into the pit and then you would be in complete darkness. When the locomotive had been serviced it was placed on a line near the shed exit known as ‘London Road’ to await its next duty.

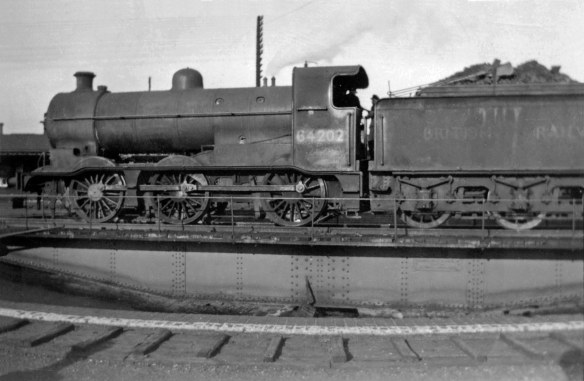

Photograph lent by Peter Wilkinson.

Photograph lent by Peter Wilkinson.

Peter recalls working as a fireman on the Stainby branch, a single-track freight only line from High Dyke. “In most of my time there was only one type of loco worked the actual branch line, the ex-G.C.R. Q4 0-8-0s. Towards the latter part of my time they introduced the O2 ‘tango’ 2-8-0s - and they even started fitting tablet catchers to them – an luxury which I never experienced! I found out why there was always a vertical handrail on the cabs of G.C.R. locos: for the fireman to hang on to with his right arm/hand whilst changing the tablet with his left. At the same time his feet were one behind the other on the four inches of footplate which ran down the outside of the cab. The tablet, which you had taken into your possession from the signalman at High Dyke, was hung onto the first post at Colsterworth by means of the large wire loop on the tablet pouch. You then bent your left arm before getting to the second post some 20 yards further on, and made sure your arm went through the wire loop of the second tablet which allowed you to go into the next section to travel on to Stainby. All the time this was going on the driver was watching you to see if you missed the second tablet. If you did miss it, which all firemen did at some time, there was much grumbling as the driver had to stop and reverse back past Colsterworth to work up speed again to get up the next incline, because Colsterworth was in a hollow. Happy days!”

This view was taken from a newly constructed gradually rising embankment for the storage of loco coal wagons which was built in connection with the new coaling plant then under construction.

Photograph by Jack Faithfull.

This image is from the collection of The Railway Correspondence and Travel Society (RCTS) ref. FAI0012 and is used here with permission.

Photograph by C.J.B. Sanderson

While he was a fireman Peter spent a week driving a J52 (ex-GNR 0-6-0ST) locomotive under supervision on the goods yard shunt. This was valuable experience, learning how to control locomotives and rolling stock with precision, obeying shunters’ signals and so on in preparation for advancement to driver. During that week, he said, “I never picked up the shovel, the driver being Norman Baines. When we drew out the tools from the stores at the start of our shift we were presented with some brown powder in, I think, old newspaper and we used to call it ‘cocoa’. This was duly placed into the water tank when preparing the loco. to prevent ‘priming', the carrying over of water with the steam into the locomotive’s cylinders, due to the surging of the water inside the boiler set off by back-and-forth movements during shunting.”

The J52 tank engines also carried out basic tasks such as positioning wagons of coal on the coaling stage. Sometimes one of these engines would be used to drag a large locomotive which was slow in raising steam, but urgently required for traffic, up and down the shed yard. The ‘dead’ locomotive’s reverser was set in the opposite direction of travel, which caused its cylinders to pump air creating a draught to draw the fire. After about six times pulling and pushing the length of the yard the fire was usually brought to life.

Photograph lent by Peter Wilkinson.

I asked Peter, in a letter, about Grantham men’s opinion of one of the smaller types of locomotive found at Grantham, the J6 0-6-0s, as shown in his photograph above. This is his reply:

I cannot recall anyone giving a J6 a bad name and, to my mind, they were an ideal loco for the work they were designed for – light passenger and goods. You could get a rough trip on any class of loco, large or small, but the J6s were pretty good at steaming. Somewhat basic in design and comfort, but they would do their job.

When you mentioned the J6 a small incident came to mind. One summer’s evening my driver (I can’t remember who it was) and I were in the loco crew mess room when the Foreman came in and instructed us to take an old Grantham favourite, the D3 class No.2000 (later No.62000) to Ancaster Bank (on the Grantham-Sleaford line) to pull in a J6 which had failed. We went there light engine and, on arrival, found that the J6 had a broken eccentric rod. The fitters had dug the broken end out of the ballast and lashed it up with rope. On the return journey we had three fitters and a bicycle on the footplate as well as ourselves. Can you imagine trying to fire with that lot on board?!

On another occasion, in the Grantham ‘Loco’, a J6 got me in a spot of bother. My driver brought this one in for coal and water rather briskly, and we were coming up to some points, which I had to run up ahead to and ‘sit on’ to turn us onto another track [this means pulling over the point lever and holding it against a spring, to maintain the points against their normal setting while the engine passed over]. I had to get off the engine whilst travelling at a fair speed and run faster than the J6…but I wasn’t quick enough. As soon as I sat on the points I knew it was a disaster. There was a sickening crunch, and next thing the J6 was nose down ‘on the muck’ as we would say. Luckily the fitters were able to block it up with wood between the wheels and the track. With the J6 in reverse and full regulator she came back on the track again. You see, good to the end!

In terms of the closing chapters of East Coast Main Line locomotive history Peter was at Peterborough with Grantham’s second last ‘C1’ (ex-GNR 4-4-2 large ‘Atlantic’) locomotive No.62810 when it was seriously damaged in a collision. The C1s were the immediate predecessors of the A1/A3 class, of which Flying Scotsman has become one of the most famous locomotives in the world. They remained on express passenger services until the 1930s.

This is Peter’s account of the incident which led to the withdrawal of No.62810:

This locomotive, together with its stablemate, No.62822, were the last two remaining at Grantham when I joined the railway as a cleaner. Their class was C1, and they were well-liked locomotives apart from their rough riding when travelling at speed, partly due to their top-heavy boilers and the trailing ‘pony wheel’ suspension. Both were ‘shedded’ at Grantham.

Photograph lent by Peter Wilkinson.

On a date which I cannot recollect in 1949 I was scheduled to book on duty with ‘Benny’ Kirk, a fairly senior Driver, and our job was to take a passenger train out of Grantham at 8.40pm to Lincoln, stopping at several stations en route. On arrival at Lincoln we were uncoupled and went ‘light engine’ to the Loco Dept. where we topped up with water and had our sandwiches on the footplate (the canteen was not open at 10pm). We reversed in due course onto a goods train which we were to take back to Grantham and straight through to Peterborough (New England). This was a recognised regular working of 6 nights per week.

We reached New England at around midnight, deposited our train in the goods yard and turned the loco in preparation for a run ‘light engine’ to Grantham. Visibility was good, but it was not moonlight. My Driver told me to telephone the Signalman at New England North and inform him we were ready to leave for Grantham. By the time I had got back to the cab of the loco my Driver had already ‘got the board’ (signal) and was rolling forwards. One got quite adept at jumping on moving loco steps and didn’t think anything of it! (No ‘Health & Safety’ then.)

It was a very short length cab on the C1 and the crew usually stood up all the time. There were very basic wooden seats, but with their tendency to roll rather violently it was safer to stand up. I stepped onto the footplate and looked through the spectacle plate (front window) to see the white light of a loco coming back towards us – too fast for comfort. We had not reached the main line and were still within the Loco Dept. I turned and shouted to my Driver, but he had already seen it and was dropping down behind the large reversing lever which the C1 was fitted with.

Within seconds there was a loud crash and I found myself half-lying, half sitting on the front platework of the tender, and the footplate was ankle deep in coal.

We found we were alright and examined the front of our engine, where the K3 class loco had collided, running tender first. The front bufferbeam had taken all the shock and was bent backwards. I remember the buffers were in quarters – the castings had cracked into four pieces. However, it was deemed by the loco fitters that it would get us back to Grantham, which it did, but the following day it disappeared and was never seen again and duly scrapped.

No.62810's stablemate, No.62822, was in use on local passenger work until late 1950 ( see Peter's photograph above) when it carried out a special non-stop run from King’s Cross to Doncaster, 'The Ivatt Atlantic Special', on 26th November 1950, to mark its withdrawal as the very last of these famous Edwardian locomotives. Follow this link for a photograph of No.62822 on the special train departing from King's Cross for Doncaster.

In May 1948 the newly-formed British Railways held a series of trials in which locomotives from different parts of the country were ‘exchanged’ onto other routes to test their capability. While he was cleaning locomotives outside the ‘Top Shed' at Grantham Peter saw Southern Railway Merchant Navy No.35017 Belgian Marine and Great Western Railway King No.6018 King Henry VI pass by on trains between King’s Cross and Leeds.

These locomotives were a big talking point at the time because they embodied some quite revolutionary design features. The 'Merchant Navies' were therefore very different from the Nigel Gresley-inspired express passenger locomotives that would normally head this Leeds to London service. However their chief designer, Oliver Bulleid, began his career as a railway engineer on the Great Northern Railway at Doncaster Works and he had been Gresley's assistant for many years until 1937, when became the Chief Mechanical Engineer of the Southern Railway. So there was a particularly keen interest in seeing how the former GN/LNER man's locomotives would perform on his old East Coast territory.

The white bands painted on the water crane at eye level are a reminder of the difficulties of operating the railway under blackout conditions during wartime.

Photograph from the J. Scott-Morgan Collection of the Historical Model Railway Society (HMRS).

Peter left the railway in August 1954 to pursue a career in the police force. Shortly before leaving, and having been accepted for the police, he injured his foot when it became trapped between the locomotive and the tender of an A4 locomotive. He went to hospital and feared for a time that it might put his new job in jeopardy, but fortunately the injury wasn't serious.

Leaving the police in 1968 Peter became Harbour Master for the Brayford Trust which manages the Brayford Basin and Lincoln Marina on the canal system in Lincoln.

In February 2023 we received the sad news of Peter's death at the age of 90. There is a tribute page here.

Copyright note: the article above is published with the appropriate permissions. For information about copyright of the content of Tracks through Grantham please read our Copyright page.

Sad news about Peter, however, he has left us some riveting reading enabling him never to be forgotten.

When you read these articles it makes one realise what those who were born post August 1968 have missed.

I can only say that Peter was a wonderful person who was kind and caring to everyone. Peter wrote a book about his personal

memories of his life - "My Lincolnshire Life" (ISBN: 978-5272-5296-7) which he gave me a signed copy at one of the "Western Front Association" Christmas Dinners that was held at the White Hart in Lincoln in December 2019. Meeting him at the meetings in Grantham with this railway group was always a pleasure to be in his company, with knowledge of railways always interesting.

He shall be sadly missed by so many of his friends.