Introduction

by John Clayson

Born in Grantham in 1923, just a few months after the London & North Eastern Railway itself came into being, Boris started work as a locomotive cleaner with the LNER at Grantham ‘Loco’ on 4th November 1940, aged 17. He gained the nickname ‘Bloge’ – he doesn’t know why, but it stuck!

During wartime, due to the shortage of manpower and the intensive use of Britain’s railways for the war effort, promotion was more rapid than had been customary at Grantham in the 1930s. So Boris became a Passed Cleaner, able to act as a Fireman, after around 12 months. He soon gained regular firing experience out on the line – much more rapidly than he would have done before the war. Promotion to Fireman came in March 1945, at the age of 21.

Lent by Boris Bennett.

Lent by Boris Bennett.

Lent by Boris Bennett.

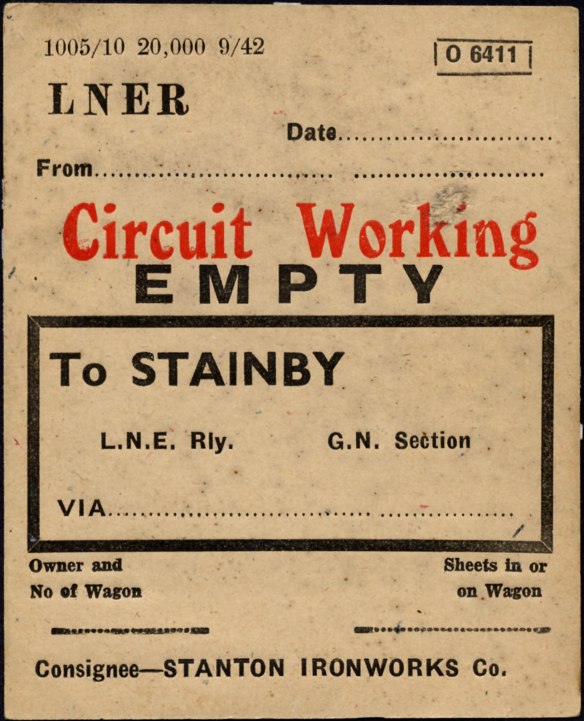

Boris remembers working up the branch from High Dyke, five miles south of Grantham, to Sproxton and Stainby, where wagons of ironstone were collected from local mines and quarries. The branch was known as ‘the Alps’ because of its steep, switchback gradients. In his day only the smaller freight locomotives (classes J6, J11, J19 and J39) were used on the branch. After the war the line was strengthened to allow access by heavy freight engines. Boris remembers that the branch was worked by what became known as the ‘old men’s gang’ of Grantham drivers – those who, for various reasons, were no longer driving on the main line. They were often paired with the least experienced firemen. About ½ mile east of Skillington Road Junction, at Colsterworth Siding, there was a water tank beside the line, carried on brick pillars. When taking water firemen climbed onto the top of the locomotive’s tender and were level with the tank. Having to wait for several minutes while the tender filled, they sometimes used this time to write notes on the tank. Boris says that the tank became something of, to use modern terminology, a ‘message board’ where young firemen communicated their thoughts on a range of topics, especially incidents and characters at ‘the Loco’, which were not for the eyes of the old drivers who never ascended beyond the footplate.

Lent by Boris Bennett.

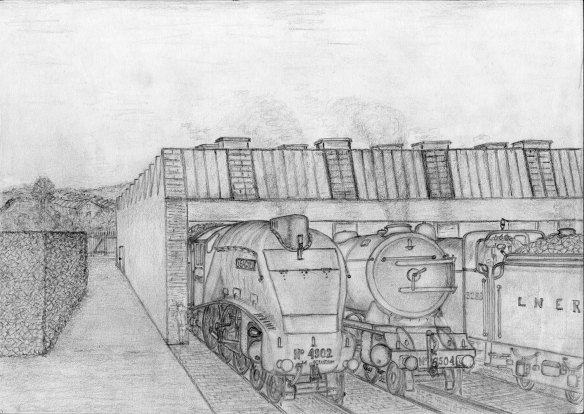

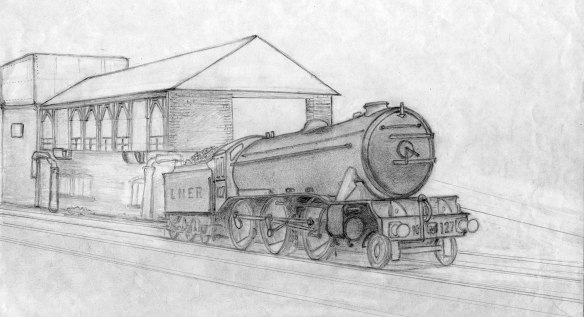

Boris has a clear visual recollection of scenes, people and events. He drew sketches to record milestones in his railway career, and he recalls two particularly memorable trips as a fireman on the main line in skilfully observed essays.

Lent by Boris Bennett.

Lent by Boris Bennett.

It is signed 'Bloge A Bennett', 'Bloge' being Boris's nickname at Grantham Loco. The date, 4.11.40, is Boris's seniority date, the day when he began work as a cleaner.

Lent by Boris Bennett.

The locomotive is painted in the black livery applied to express passenger locomotives during the second world war, both as an economy measure and to make them less identifiable from the air.

Lent by Boris Bennett.

Boris resigned from his job on the railway in 1947 because the constant shift work was too restrictive of social and other activities he wanted to pursue. 70 years on from those days the memory of his years on the footplate and around steam locomotives remained vivid. This is how he summed up his time at Grantham ‘Loco’:

In my short stay there I learnt a lot about the job, about life and about the men I worked with, whom I have never forgotten. It opened my eyes to things I hadn’t realised before.

Lent by Boris Bennett.

Postscript

Sadly Boris Bennett passed away in June 2015 at the age of 91. I first met him in July 2013 and later that year he very kindly welcomed me at his home. On that visit, and subsequently, we enjoyed long and fascinating chats about his life in Grantham, particularly his time as a young man working on the railway. The above introduction is based on notes made during those conversations. Boris was already well on with writing up the two footplate experiences that follow (below). It was a privilege to transcribe them, on his behalf and with his blessing, into a format which can be widely read, appreciated and enjoyed.

Footplate Experiences

The following two accounts of experiences on the railway were written by Boris and he kindly gave permission for them to be published. They illustrate the dependence of the railway on teamwork and communication between the various grades of staff such as footplatemen, shed staff both in the office and ‘outside’, signalmen, engine changers and station staff. Both trips include night-time working, and there are perceptive descriptions of the sensations of steam locomotive footplate work during the hours of darkness.

These stories also bring to life for us some of the characters of Grantham’s railway community showing, on one hand, how people respond in adversity to ‘keep the job running’ and, on the other, the occasional moment of ‘straight talking’ by one colleague to another, in this instance after a particularly wearying trip when a rival depot had conspired to replace a sound locomotive with another which was not up to the job.

Note: At the author’s suggestion a few examples of ‘strong language’, which are in the original scripts as an accurate record of events, have been moderated - even though, in modern day terms, they are relatively mild in nature. This is partly because we want people of all ages and stages of life to have access to these stories. However another, equally compelling, reason applies. The men whose words are quoted seldom employed so-called bad language outside the company of their workmates, and certainly not at home or, knowingly, within earshot of children and young people. Having worked alongside them Boris felt that, if they could be asked, they would prefer that such language, though common currency in the workaday and private world of the footplate, and recorded by him accurately as such, should not be included as direct quotes in a public forum.

1. A Bad Wartime Trip with a ‘Jazzer’

by Boris Bennett

In April 1944 I was working with Driver Arthur ‘Prince’ Measures. For a week we were booked every day on a somewhat nondescript turn of duty. We were to sign on at 7.35pm, relieve New England (Peterborough) men on a parcels train in the Western Platform (No.5) at around 7.45pm and work forward to Doncaster, calling at Newark and Retford. Upon arrival we were relieved by Doncaster men who worked the train forward from there. There was no booked return working so we travelled back to Grantham by passenger train.

If the parcels train was on time into Grantham when we took it over we were only about halfway through our shift when we were relieved. On arrival back at Grantham this usually meant that we had about three hours to do ‘in Loco’ until the end of our eight-hour shift at 3.35am. This wasn’t a good way to finish one’s turn of duty as it normally consisted of less than pleasant ashpit, disposal and preparation duties.

On the Wednesday morning, when we were booking off duty in the time office, Arthur went to have a look at the duty list for the next day. He shouted me over. “Look here mate, we’ve got a mileage trip tomorrow.” It was a back working from Doncaster through to Holme, some six or eight miles south of Peterborough, returning to Grantham tender first with the empty stock. This would give us a round trip of about 195 miles. Pay was calculated on the distance worked in excess of 125 miles, which was paid at the rate of one hour for every 25 miles, so this trip would work out for us at more than two hours' extra pay. What was more, we would sign off when we returned to the Loco, regardless of how long it took us to do the job. Arthur reckoned we could be back by about 2.45am, and with that we set off home. “Good day kid, don’t be late tonight,” was Arthur’s parting remark.

We signed on at 7.35 that night and duly relieved the New England crew. We were right time and arrived in Doncaster at 10:30. We reported to the loco inspector on Platform 6. “Now driver,” he said, “We have got your engine ready for you in the up dock.” As we made our way to the engine Arthur muttered, “That’s blxxxy queer, this train’s supposed to start from York. Why are we getting a fresh engine from here?”

As we approached the engine stood in the dock. I could see that it was a K3, otherwise known as a ‘Jazzer’, No.127 allocated to Immingham.

For an introduction to the K3 locomotives see this page. No.127 was later renumbered No.1878 (1946), then No.61878 (1949). There’s a photo of 61878 behind sister loco 61975 here.

Lent by Boris Bennett.

“That’s it,” said Arthur. “These crafty bxxxers are going to collar that train engine and palm us off with this crab.” As we changed over with the Doncaster crew and climbed onto the footplate I realised the wisdom of Arthur’s words. The fire was a dull red with a sprinkling of black over the surface. I thought that the dampers must be shut. However I soon found out that was not so. The gauge lamp burned as dirty as the fire and all the steam gauges had faces as black as their needles, a sure sign that this engine was not in very good nick. The boiler pressure steam gauge showed 155 psi. ('psi' is pounds per square inch; the normal working pressure of K3 locomotives was 180 psi.) I decided to try and liven up the fire, so I gave it a stir up with the pricker and a quick round of coal without much success. The fire didn’t revive a great deal although she began to make steam. Arthur was still chuntering about those Doncaster blxxxers doing it on us. Suddenly he said to me, “When our train runs in, kid, nip over and see what engine he has got.” Sure enough, at the head of our train was a ‘green arrow’ with the words ‘V2 NEW ENGLAND’ on the buffer beam. I ran back over to our engine in time to see the dolly come off for us to pull forward before reversing back onto the train, the green arrow having come off and gone to Carr Loco.

We reversed onto the train, which was full of American servicemen, and were coupled up by the engine changer. I removed the tail lamp from the tender, altered it from red to white, put it on the left front lamp iron and returned to the footplate. A few minutes later we were ‘right away’.

It wasn’t long before we found out why we had finished up with this engine. A quick look at the steam gauge showed that we were steadily losing pressure and, no matter how I fired, she continued to lose out. The water in the gauge glass was getting lower and lower and I had yet to put the injector on. Arthur said that if we carry on like this we shall be inside at every loop from here to Holme – that’s if we don’t stop on the main line for a ‘blow-up’. I gave her another round and got the exhaust injector working. Had another look at the pressure gauge – down now to about 130 psi; we were plodding along like a three-legged donkey and losing time hand over fist.

By this time things were getting serious, for without doubt we were going to be stopping some of the following express trains. Sure enough, as we approached Ranskill the distant signal was against us and we were duly ‘put inside’ there.

Well, to cut a long journey short, some hours later we found ourselves inside at Barkston, thoroughly fed up and very disillusioned. Arthur said, “We shall have to get the pilot [spare engine] at Grantham.” At that moment the ‘Newcastle’ came thundering by, followed about 10 minutes later by another Up express. I said to Arthur, ”That one seemed to be making hard work of it.” We had got round to 150 psi when the board [signal] came off for us and we set off for Grantham, whistling ‘three crows’ for the pilot as we passed the box. We arrived at Grantham South box in dire condition, with steam pressure at 100 psi, 1½ inches of water in the glass, but anticipating that we would be getting shot of this crab and getting the Grantham pilot for the forthcoming five-mile climb to Stoke Tunnel.

Not true. What we did get was running foreman L. Sprague with the news that the labouring express that passed us at Barkston had taken the pilot. “That’s it,” I said to Arthur, “I’m going to clean this blxxxy fire before we go any further.” To which he agreed.

That having been done and with a full boiler of water and 175 psi of steam pressure, Arthur whistled for the board and we were away. By the time we reached Ponton I was in trouble again. Steam pressure was down to 120 psi and half a glass of water. At High Dyke we were turned into the slow road and stopped for The Aberdonian, which we had delayed on our way up the bank. “Well,” said Arthur, “At least we just need to get through Stoke Tunnel and we can have a blow down to Peterborough.”

Well, we eventually arrived at Holme and the Yanks detrained and went on their way. It remained for us to work back to Grantham tender first with the empty stock. Following a futile request for the pilot at Peterborough North we eventually arrived at Grantham, stopping halfway down Platform 3 prior to shunting the stock into the carriage sidings at the South Box. The time was about 10.20am; we’d hoped to be signing off at 2.45. As we waited for the dolly [shunting signal] and the tip from the guard, ‘Prince’ was assailed by an irate Platform Inspector who, waving his arms around, proclaimed that we were 'stopping the milk’. Arthur was sitting with his back to the cab window, enjoying a pipe of bacca. He spun round on his seat to face the Inspector, removed the St. Bruno incinerator from between clenched teeth and, pointing the sucking end at the man, said, “Ah, and now I’ll tell you summat mate, should I? Before you got out of that nice warm bed and came here to play Station Gaffer we’d stopped the Newcastle, The Aberdonian and the blxxxy Colchester. Stick yer ace of blxxxin’ trumps on that!”

As we parted at the Loco entrance on Springfield Road Arthur said, “When I’m drawing my last breath I reckon I shall see that No.127 floating before my eyes!”

Driver Arthur 'Prince' Measures

Driver Arthur 'Prince' Measures, to whom Boris fired on the trip described above, worked at Grantham for the Great Northern Railway, the LNER and British Railways Eastern Region. The photograph below was taken to mark his retirement.

Also present are (left to right) ASLE&F Organiser Councillor W. Bevan, Driver Fred Seal, Shed Foreman Fred Blanchard, Grantham Shedmaster Gordon Glenister (at the back, without a hat), Chief Mechanical Foreman Cyril Richardson and acting Running Foreman Reg Earl (wearing a flat cap).

Arthur Measures was born in Sleaford on 17th August 1887. In the 1911 census Arthur was a Railway Engine Cleaner, lodging with a railway porter and his family in Grantham. During the 1920s 'Prince' Measures was one of the regular firemen of Grantham-based Gresley pacific No. 4479 'Robert the Devil', and he would have been a footplate colleague of Driver Charles Parker who has a biographical page here.

Photograph by The Grantham Journal.

2. Firing a ‘Green Arrow’ to York

by Boris Bennett

This is an account of a turn of duty that took place in September 1945, four months after the end of World War 2 in Europe. It was an experience familiar to many footplate crews on the LNER in those days, although on this occasion the outcome was not as anticipated.

The time was about 10.20pm on a Monday night in September 1945 as I started the short walk from my home at 49 Stamford Street to the LNER Loco running shed at Grantham. I was booked on duty at 10.32pm, engine prepared, to work the 11.08pm to York. The engine would go through to Newcastle.

As I crossed Springfield Road to enter the Loco gate I was accosted by some of my dayshift mates returning from their revels at the local pub. They were quick to let me know that it was better to be off to bed than where I was going. I laughed them off with the reminder that they would be going the same way next week and went on my way.

The night was cold and clear but intensely dark, just a few stars visible in the sky. I continued on my way past the Top Shed. Outside the shed, staff were busy about their duties disposing and preparing engines, their flickering flare lamps now in full use after the relaxing of wartime restrictions. I wondered, “Would we get one of the pacifics being prepared there to work our train?” I was soon to find out.

I arrived at the time office in good time and signed on. The time office was a wooden building situated between the blacksmith shop and the Old Shed, opposite the coal stage. It was from there that all the work of the depot was organised, it being the location of the running foremen, time checkers, cleaners’ chargehands and the time office runner – a dogsbody who delivered the fitting staff their work cards, and did general messages and called out of engine crews at their homes when their duties had been altered.

My mate, Driver George Newbury, came in two minutes later and signed the duty sheet. George was rather short in stature, a little on the stout side, with a round face that always seemed to me likely to break into a grin at any moment and a somewhat swarthy complexion. At any time he could be seen smoking one of his favourite woodbines, which he seldom removed from his lips until it was spent.

George stated to read the permanent way notices. After he finished he turned to me and said, “Are we fit, kid?” “Just about, George,” I said. “I don’t know which engine we have yet, though.”

At that moment running foreman Cyril Richardson appeared through the office door as he went on his rounds. “Which one have we got, Cyril?” asked George. “You will have to take the pilot, mate. That’s the only one we’ve got at the moment, No.3656.”

No.3656 was later renumbered No.929 (1946), then No.60929 (1950). There’s a photo of it as 60929 here.

Lent by Boris Bennett.

Perhaps I should explain the circumstances that prevailed on the railways at the time. For the previous six years of World War 2 the railways had been running with an almost total lack of maintenance and renewal. Track and locomotives were in general in a run-down condition. Engines had been called upon to perform feats of haulage far beyond the specification for which they were designed, from the little 0-6-0 ‘B’ engines right through to the great A4s, A3/A1s and V2s of Sir Nigel Gresley.

Here is a link to a photograph of 'B' engine No. 4040 (LNER class J4). [Sorry, we've removed this link as the photo no longer appears to be available.]

The V2s in particular seemed to turn up on almost any type of train, but mostly on express passenger, No.1 express freight or a trooper, though I have also seen them on class C loose-coupled mineral or ironstone trains. During my time as a fireman there were never any of these V2s allocated to Grantham but at any time you could find five or six of them on shed. They were indeed a fine engine.

In those days running shed foremen who found themselves stuck with an engine in poor condition would put it on a turn where hopefully it would be returning home, or to some other depot. Thus if it was likely to fail it would not be on their territory, the failure rate being higher than normal in those days of low maintenance. It was not unusual, therefore, for enginemen to be landed with one of those run-down engines. It was with this in mind, I think, that my mate had voiced his disapproval of this engine, saying that it had already been seventeen hours since it had commenced duty. It had been static for that time, but water and coal would have been used and the fire would have been damped down and somewhat sparse as there was no need for steam to be produced.

I left George in the time office talking to another driver. “I’ll nip round to the stores and pick up the ‘white uns’ mate.” “Right kid. I’ll be round in a minute,” he replied. I called at the stores and continued on my way round the coal stack to the pilot road. As I turned to cross the line I could see, in the pale light of a solitary gas lamp, a grimy, uncleaned ‘green arrow’ (V2). There were only two places where there was evidence of a cleaner’s cloth – the number on the cabsides and the letters ‘N E’ on the tender. This confirmed our fears that she was in a very run-down condition. A wisp of steam was blowing through the right-hand injector overflow, and hissing at the cylinder cocks told us that the regulator valve was blowing through.

I climbed up onto the footplate. A glance at the steam pressure gauge showed we had 130 psi. (the boiler working pressure of V2 locomotives was 220psi.) and half a boiler of water in the gauge glass. In the firebox there was a scattering of small clumps of fire over the bars and one large lump just under the brick arch, with a few flames licking round it. A soot-stained white enamel plate with black lettering announced that she was allocated to Heaton shed in Newcastle (but see the note at the end of this story).

I obviously had some urgent work to do before we could work the train. I took the pricker, spread the fire over the bars and broke up the large lump, which burst into flames. I covered the bars with coal, turned on the jet (blower) and closed the trap (an air inlet in the firehole door). At that moment George appeared and asked me to pass him down the oil feeder. “How’s she looking, kid?” he asked. I told him we needed coal and water. “I’d better see Richie and get us a path onto the pit,” he said, and off he went.

I took another look at the fire. It was beginning to burn quite brightly now, and she was making steam – 145 psi. I checked the injectors and they were both working OK. The drop bar key and spare firing shovel were in their places as were the fire irons. I swept the footboards with the handbrush that my mate had chucked on the footplate and swilled them down with the slacker pipe.

George reappeared, climbed onto the footplate, blew the vacuum ejector and set back over the points. As she started to move backward when we passed over the joints in the rails the cab top rattled and flapped alarmingly. Some bolts must have loosened with constant vibration. A closer inspection of the footplate showed that the cabside fixing on the back of my seat had pulled away. The top gate to the coal space on the group standard tender hung at an angle on one hinge, fortunately wedged there by the weight of coal pressing against it.

We set forward. The swinging handlamps of the shed staff called us on and we were turned onto the ashpit. I climbed quickly onto the tender, put the bag in the tank and filled up. Next George set back under the coaling plant and I topped up the tender with coal.

There was now a sense of urgency about our movements because it was getting close to train time. The shed staff turned us off the pit and we made our way to the Loco outlet and stopped against the telephone. “Better ring the bobby,” said George. I climbed off the engine, went to the phone and rang North Box. “Engine for 11.08 Newcastle,” I said. Back came the reply, “Hang on fireman, your man has just run in. Wait until I get shut of Cockney and I’ll have you out on the main line.” Back on the engine I told George what we were doing and we waited for the signal. It came off moments later and out we went onto the main line over the points and set back towards the train. Called on by the engine changer’s swinging lamp we rolled back gently and buffered up.

I got off the engine and went to the rear of the tender to remove the tail lamp. As I did so I enquired of the health of our mate the engine changer who, by now, was lost to sight between the tender and first coach. His handlamp, which stood on the platform, gave him little or no illumination at all. It turned out he was none other than our old mate Phil Ingleton, a very outspoken gent who would soon let you know his opinion, like it or not. He was wrestling with the engine coupling. “There’s more blxxxy grease on this coupling than in a bag of Mother Nicholls’ fish and chips,” he said. George responded smartly to Phil’s bellowed request to ‘ease up’ the engine to depress the springs of the tender and coach buffers. Phil screwed the coupling up tight, connected the vacuum and steam heater pipes, scrambled up onto the platform, wiped his hands on a grubby cloth and took off down the platform.

I went to the front of the engine, put the lamp on its lamp iron, returned to the cab and closed the doors. Looking back down the platform I could see the lights of the porters’ handlamps bobbing to and fro, and hear their shouts as they called our destination and stops en route, interrupted by the intermittent slamming of carriage doors. Soon the bustle and movement down the train subsided and the platform seemed almost deserted, save for those handlamps shining through the darkness.

The shrill blast of a whistle shattered the cold night air. Almost immediately the lamp at the far end of the platform turned green. My mate was blowing the large vacuum ejector, eyes fixed on the flickering train pipe needle on the vacuum brake gauge. The platform inspector standing close by shouted “Right Away, driver!”

George, woodbine protruding between pursed lips and still gazing at the vacuum gauge with some deliberation, wrapped his white cloth around the regulator handle and, with a hefty pull, heaved it into the fully open position.

Lent by Boris Bennett.

As the main steam pipe came up to boiler pressure the snifting valve snapped onto its seat, the needle of the steam chest pressure gauge shot round to a reassuring 200 psi, and No.3656 took up the slack in worn big ends with a resounding clank! Up at the front end came the howl of high pressure steam squeezed through a blow in one of her front cylinder covers. She started to move forward with a long, laboured blast of exhaust at the chimney, followed by two short, sharper blasts. On the footplate there started a rapidly accelerating shuddering sensation.

Suddenly the six great driving wheels lost adhesion on the greasy rail. A great cloud of smoke and steam erupted skyward. I made for the dry sand lever and with my head stuck out of the cab window, pumped away. On the platform wall opposite, flailing connecting and coupling rods were silhouetted by the red hot coals shaken through the firebars into the ashpan and out through the open damper onto the ‘four foot’. George muttered a vague curse as to the authenticity of No.3656’s origins and quickly closed the regulator. The crescendo ceased as suddenly as it had started.

George had the regulator wide open again instantly. I took the shovel and had a quick look at the fire. It was a little sparse under the brick arch so I decided to push some fire forward with the pricker. As I did so the subdued lights of Grantham North box slipped by over my left shoulder. I returned the pricker to its stowage and gave her a quick round of the firebox. She was picking up nicely now and accelerating with every second. She did a little slip as we crossed the points, which my mate soon got under control. A glance at the boiler pressure showed 210 psi.

George linked her up a couple of turns – we were beginning to get along nicely. The rhythmic sound of the exhaust that has become known, to those good folk who today enthuse for the sight and sound of the steam locomotive, as ‘the Gresley beat’ echoed out over the near-deserted streets of the town. George turned to me and, with a broad grin and a knowing wink, announced “She’s got 'old of 'em now, kid.”

We were nearing Peascliffe Tunnel at speed, well linked up. She was running very freely - somewhat surprising to us since we were expecting a rough ride due to her run-down condition. However, loose bolts, slack big ends and a number of unidentified rattles did occasion some thought as to whether she would last out to Newcastle. We plunged into the tunnel, whistle shrieking, rattles and bangs amplified by the confined space. The soot-stained bricks of the tunnel flashed by, illuminated by the light from the fire. We came out into the cold night, downgrade past Barkston South Junction and through Hougham station where engines on the down main line, for some reason, rolled alarmingly as they passed through the platforms.

She was really flying now and, since we were going downhill, George had her down to half regulator. “There’s one thing about this one, mate - she’s a good runner,” he said. A few minutes later we were passing Claypole and running in on the approaches to Newark, which was our first stop.

We came to a stand at the end of the platform. Though I had done little firing since we left Grantham she was still full of steam and water. I just needed to build up the fire ready for the six mile level run to Carlton on Trent, during which we would take water from the troughs at Muskham. As we got the ‘right away’ from Newark George enquired how much water we had in the tank. I opened the water gauge on the tender – we had about 1,750 gallons, just below half a tank. We would need to top up the tank on the troughs. I told George of the situation. “Right mate,” he said. “I’ll give you the tip when we’re half way over and that should fill her up.” I dropped the scoop in on George’s sign, but almost immediately he told me to wind it up again, with the terse observation that we were putting more water into the six-foot than was going into the tank. In our haste to get out on the train both he and I had omitted to check the water scoop nose. It had clearly been damaged on some previous journey, a frequent occurrence in those days, and we couldn’t pick up water. This meant that we would have to take water at our next stop, Retford. This would not cause us much of a problem, except that our time for the stop was limited. As we met the rising gradient through Crow Park and up by Dukeries Junction she was still steaming freely and, as George said, ‘Running like a Stag’. Minutes later we were passing Markham Box and were rushing through the short tunnel at Askham, thence down the bank into Retford.

George made a great stop opposite the water column. I nipped up the tender back and put the bag in. As I stood waiting for the tank to fill I glanced to my right – the light from the fire sent a bright finger of light into the sky whilst the steam from a partly lifting safety valve wafted into it. We got the ‘right away’ and proceeded to York, where we were relieved. The relieving fireman moaned about the poor state of the engine, but I was able to tell him not to worry – she was a good engine, and if we had engines even half as good as this one for the rest of the week I would be very happy.

Note: Information available on the Internet in December 2013 here suggests that No.3656 was a York engine from July 1941 to July 1952. We leave the reference to its Heaton allocation in place because that is the author’s clear recollection. Research into locomotive allocations using official records and other sources, and the publication of the results, is extremely valuable, though it can never be considered complete and remains open to alternative sources of information. For the purpose of this story we leave the allocation as it was written by Boris, while drawing attention to the published list. Neither is disputed and, in any event, the issue is very much incidental to the narrative.

Boris's well-described experiences took me straight back to working on the Stainby branch myself, with the ex-Great Central Q4 0-8-0s which we had in my time (1948 to 1954).

I also enjoyed reading the article A Bad Wartime Trip with a 'Jazzer'. I often wonder what it must have been like being a Footplate man in wartime. I 'take my hat off' to them all, especially in the blackout conditions of the early war years. I don't know how they did it. It reminded me of one of my trips, on a train of ironstone empties returning to High Dyke from Scunthorpe, when I was down to 60psi of steam at Barkston on an Austerity.

George Newbury - I can see him now, and also hear him, from Boris's description!